“Support local” has been a rallying cry across the country over the course of the pandemic. In Nova Scotia, that means weekend shopping at the farmers market, raising a cup of craft-brewed beer, and shelling out for the locally caught seafood.

But where supporting local seems to come to a grinding halt is in the forests. For many, it seems, wood products do not fall under “grow and process local.”

It’s an issue the province’s forest industry has grappled with since news broke in 2020 of the shutdown of Pictou, N.S.-based Northern Pulp – a key player in the forest industry as a massive consumer of low-grade wood.

Without an alternative to the income Northern Pulp provided to logging contractors and woodlot owners, forestry in Nova Scotia is transitioning to a much smaller industry with fewer and fewer players.

The co-owners of a 21-year-old Nova Scotia logging company, Next Generation Forest Management (Next Gen), have witnessed many forestry contractors quietly downsize, have equipment repossessed, or auction equipment and close up shop. It’s a reality that Calvin Archibald, 77, and Mark Bannerman, 45, are hoping their company’s experience, reputation and work ethic will allow them to survive.

Company history

Next Gen came about in 2001 as a handshake agreement between Archibald and Bannerman. Archibald had just handed over the keys of his first logging company, owned with his brother, to his sister-in-law. Intending to retire, he suggested a new company with Bannerman as a retirement project. But forestry and farming is in Archibald’s DNA, so, 21 years later, he’s still at it, taking care of Next Gen’s books and negotiating contracts.

The company’s succession plan was always for Bannerman – a University of New Brunswick forestry graduate – to grow ownership through what Archibald calls “sweat equity.” That work ethic is what grew Next Gen’s reputation in the industry, he says.

Next Gen started up with a focus on commercial thinning, which was a rarely used harvesting method in Nova Scotia at the time. The company’s wheeled 2001 Timberjack 1270C harvester and Rottne forwarder were running in a province full of feller bunchers and processors.

“I didn’t really know what we were getting into. I didn’t have much of a mechanical background, for sure. But it was an opportunity and something to try so we went at it,” Bannerman says. “There were some… but not many contractors had wheeled machines. Most were tracked.”

The company grew over the years, purchasing some new, but mainly used equipment to help keep costs low.

Like many contractors, it was a family business. Bannerman’s father, Donnie, ran a forwarder for Next Gen for 18 years, retiring three years ago at 70. His wife, Selena, as well, did some forestry and mapping for the company for a few years before returning to school to get her education degree.

Today, Next Gen is among the largest contractors in the province with eight operators and a mechanic on the payroll. They’re running six harvesters daily – a Ponsse Ergo and three Fox, a Komatsu 901 and a John Deere 1170 – as well as two John Deere 1510 forwarders. A spare Fox harvester and 1510 forwarder are used as needed.

Bannerman is quick to jump in a machine for the day if needed. “I do the odd shift to fill in. If somebody’s off, sick, or we’re between employees, I’ll try to make sure the machines aren’t sitting,” he says.

Next Gen’s senior employee of 19 years, Grant MacDonald is an important part of the company. Grant has transitioned from operator to full time mechanic and parts manager.

Next Gen averages around 90,000 cubic metres per year, much of which is small wood around 0.06 piece size. Most of their stud wood goes to Scotsburn Lumber and the pulp to Port Hawkesbury Paper in Cape Breton.

Forest practices transition

Nova Scotia is also going through an overhaul of forest practices. The province’s stated goal is to revamp forest management, prioritizing conservation and biodiversity through lower impact harvesting. The new forest practices guide is based on a 2018 report from William Lahey, president of the University of King’s College in Halifax, that recommended forest practices that would balance environmental, social, and economic objectives.

From left, Dave Boutilier, Mark Bannerman, and Duncan Cameron on a harvest block in central Nova Scotia in early May.

As a trained forester, Bannerman says he supports the conclusions in the Lahey report. “Our operators have the skills to implement any kind or treatment, as long as it is economical,” he says.

But an inherent contradiction of the government’s policies is that prioritizing biodiversity and a return to higher-quality Acadian trees requires the removal of low-grade pulpwood.

“When the pulp mill was there, you could go into a woodlot and pay a decent stumpage rate for low-grade species. If you were doing a thinning job and there’s pulp you knew you could get rid of it. Now a lot of that is just left behind or not cut in a lot of areas of the province,” Bannerman says.

Biomass harvesting, as well, is not typically economical with few large-scale customers in the province.

What’s working?

Before Northern Pulp closed, a large portion of Next Gen’s work was commercial thinning for the pulp mill. Now, the company does a variety of harvesting treatments mainly for Wagner Forest Management based in Truro, N.S.

Next Gen runs six harvesters and two forwarders daily, employing eight operators and a mechanic.

“We’ve had little change in our employees. We were lucky enough to find work. Eighty per cent of our harvesting is for Wagner and we do some private woodlots still,” Bannerman says.

One continual strength for Next Gen has been their operators. Over the years, as many contractors struggled to recruit and retain operators, Next Gen has had to fill only a few seats.

“The operators are what keep us going, they’re the main reason we’re still in business,” Bannerman says. “We try to work as close to home as possible. We can balance out the shifts or maybe work an hour less a day so they can get home on time. And we’re pretty flexible if people need time off.”

Harvester operator Duncan Cameron has been running forestry machines for 16 years, mostly with Next Gen.

“For me, now, there’s a good work-life balance,” Cameron says. “I think it goes for anyone here, if they need a day off or you need to be somewhere, you can take it. There’s no big issue.”

Next Gen has a few younger operators as well. Archibald credits the Canadian Woodlands Forum for supporting the contractor communities in Atlantic Canada and helping draw in and train younger operators.

What’s next?

Archibald says he sees a future for Next Gen, but that all depends on whether or not there will be a healthy future for forestry in Nova Scotia.

Before Northern Pulp closed, much of Next Gen’s work was commercial thinning for the mill. Now, the company does a variety of harvesting treatments, mainly for Wagner Forest Management based in Truro, N.S.

“We named it Next Generation on purpose,” he says. “A lot of forestry companies are one or two generations at the most. We wanted an organization that would last beyond our generation and also the generation of trees.”

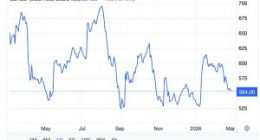

But some things are simply out of their control. A recent economic study shows a dramatic decline in Nova Scotia’s forest industry over the past few years.

“A lot of people just don’t understand the forest industry,” Bannerman says. “Our forests are a renewable resource that can supply jobs and sorely needed government revenue especially post pandemic. It doesn’t seem like recent governments publicly support forestry. They should have worked closer with forest companies to create markets and ensure a strong industry after the closures of Northern Pulp and Bowater.”

Both Bannerman and Archibald note that forestry stakeholders need to do a lot more to educate the public, and that will take work.

“Forestry workers tend to put their heads down and go to work to support their families. They aren’t out there publicly advocating for the industry. We need more of that, but most aren’t comfortable doing it, including myself. I’m not an outspoken person,” Bannerman says.

It’s difficult to rally when contractors are feeling more than a little defeated in the province, Archibald says. But Next Generation is the name, and the company has positioned itself to weather this storm.

“We’re successfully maintaining used equipment, and you combine that with our ability to negotiate and Mark’s and our crew’s top-notch reputation . . . we’ll be here for a while,” Archibald says.